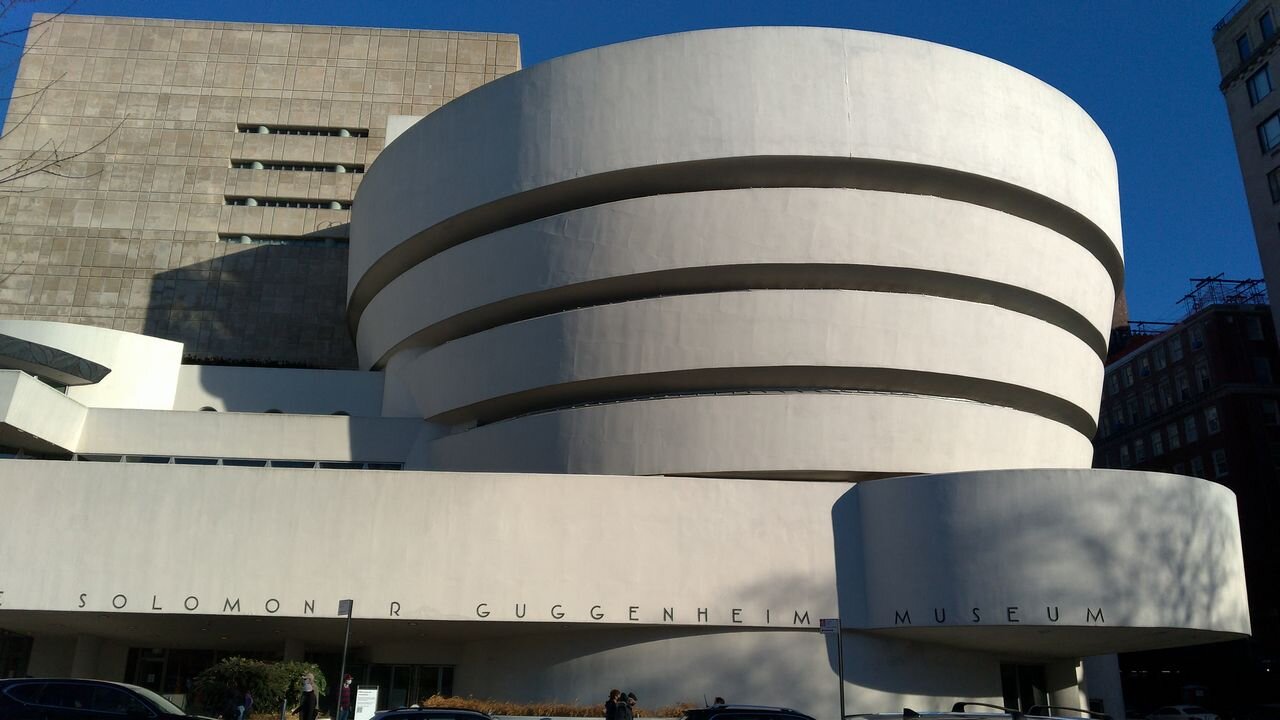

A hint of claustrophobia gave me pause when the “Napoli Sotterranea” tour guide described the very narrow and dark passage that was coming up and which we were supposed to cross in single file and with our flashlights on. I'm sure I'm not claustrophobic, yet I decided not to proceed along with the other visitors. Maybe the real reason was the desire to enjoy the gigantic, cool subterranean “arcade” on my own and in quiet -something otherwise impossible during a group tour.

After having spent seven days in the heart of Naples, on the eve of my departure, I finally enter the... inner sanctum. With roots spreading thousands of year ago, underground Naples and its maze-like network of huge caves encompasses three primary uses: ancient Greek quarries, Roman aqueducts, World War II bomb shelters. In the “lower” city, in the monster's belly, I'm given the opportunity to “digest”, to mentally organize the overwhelming impressions from the “upper” city with the thousand faces.

COUNTLESS CHURCHES

Necks ache from a week's worth of gazing up at the stunning interiors of the countless churches (there are literally hundreds of them): the dazzling frescoes, golden arches and incredible splendor in Gesù Nuovo's dome; the breath of David and Jeremiah's sculptures (you think they're about to detach themselves from their niches and take flight) in the same church; Perugino's “Assumption of the Virgin” in the Duomo; the masterful marble sarcophagi in San Lorenzo Maggiore; the deliciously delicate decoration in San Giovanni Maggiore, with the pastel motifs curling around capitals and ceilings like fragile paper wrap of luxury pastry.

Architectural movements and historical layers pile up not only in churches but also in palaces, theatres, towers, obelisks, castles, monastic complexes, while the momentum of the contemporary city keeps you alert, since the ceaseless flow of pedestrians and vehicles is exhausting and often dangerous (every night I thank God that I didn't get hit by any of the motorcycles that rush day and night at a hair's breadth by the tourists on the bumpy, preserved cobblestone narrow streets of the Centro Storico).

LAUNDRY AND SOCCER

Striped awnings and colorful loads of washed laundry blow eternally in the wind, but now on the clothesline ropes that connect one historic residential building to the other have been added thousands of white and light-blue celebratory ribbons, as an homage to the recent Napoli soccer team's championship, accompanied by libations of Maradona Spritz at the bars and the Argentinian's portrait bearing a halo featured on graffiti and banners.

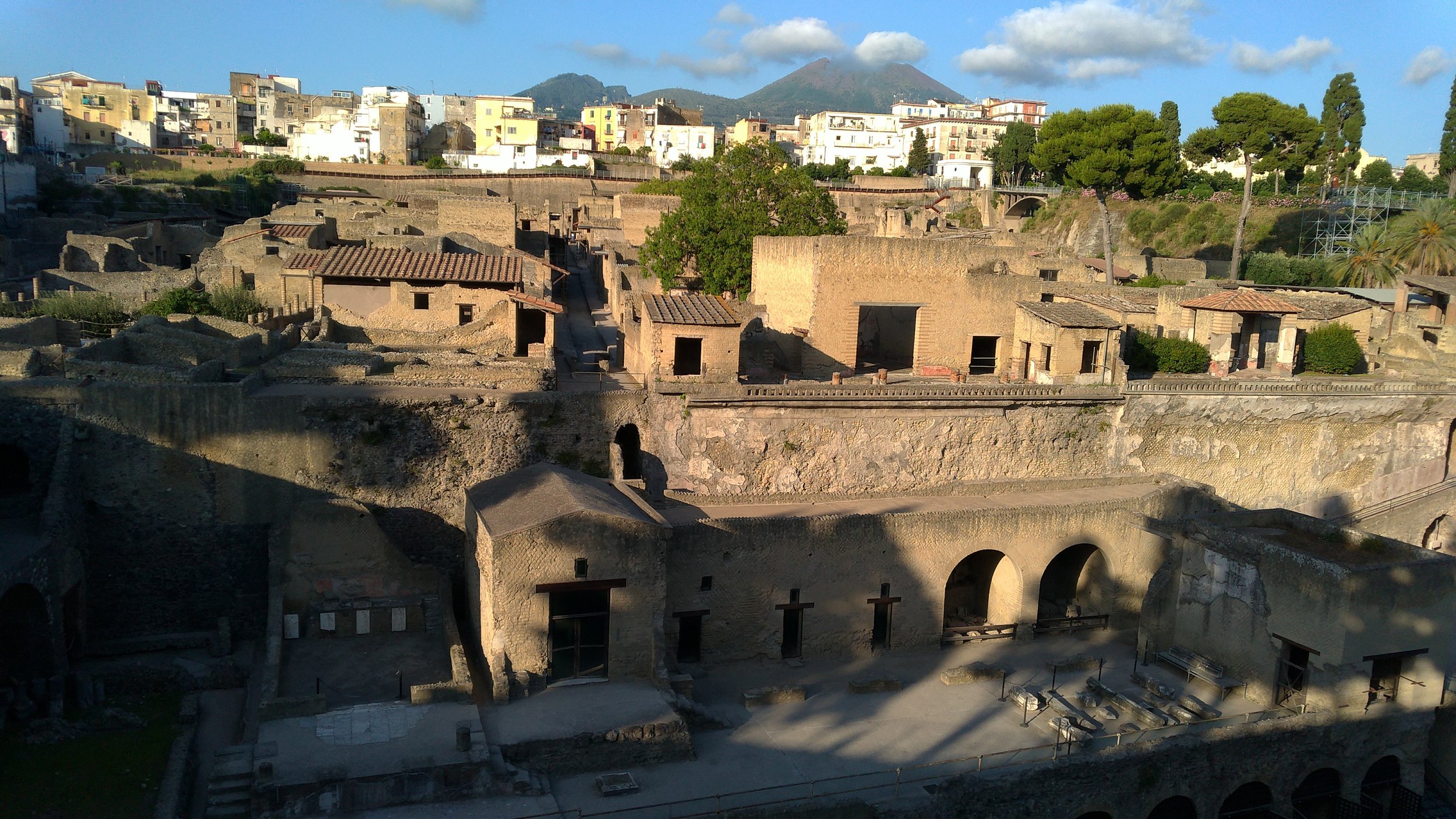

But here in the earth's guts I also have the chance to recall yesterday's archeological excursion: the first thrill once you arrive at Herculaneum (modern-day Ercolano) on the Circumvesuviana train – just a twenty-five minute ride from Naples – comes from reuniting with the sweetness of the Mediterranean summer thanks to the reconnection with nature: the bright green of the familiar pine trees, the accompaniment of the cicadas, the dear pink of the oleanders. Even the afternoon sun feels milder in the open country of Campania than in the thick Neapolitan urban matrix.

UNTOUCHED CITY

The Herculaneum archeological site introduces itself very straightforwardly to the visitor: skulls and skeletons belonging to the inhabitants of the once-upon-a-time thriving Roman city “greet” you at the facade. Those people had sought refuge in the boat sheds situated at the edge of the city, along that era's coastline, when Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD. They perished right there, buried under the volcanic ash which, ironically, proved lethal to their individual existence, yet offered immortality to the material aspect of their organized social life: thanks to the otherwise deadly to mortal humans tephra, their exceptionally developed city remained astonishingly untouched for 2000 years.

I walk along the House of Argus colonnade and I picture the symposia it would have framed. I caress the deep-red wall of a nearby room and I marvel at the playful “reflection”, since the painted decoration depicts a peristyle.

Little dolphins, an octopus, a squid, all of them are “swimming” around a Triton: the immaculate joy of the Mediterranean summer jets out of the two-thousand-year-old spectacular mosaic floor and inundates the Thermae. All my imagination needs to supply is the water. I place my (imaginary) aryballos on the perfectly preserved little shelves of the apodyterium and I get ready to “dive in”.

Fully immersed by now, I exit the frigidarium and I pay a visit to the House of the Wooden Partition. I sit by the impluvium (a basin for collecting rainwater) at the center of the enormous atrium and I gaze at the splendid fresco. I wonder whether this luxurious villa's former inhabitants too loved the same tiniest detail -a small strange blossom. The house is packed with guests, that's why the hosts have retired in the special area which, thanks to two sliding wooden doors, is separated from the imposing reception room. I'll ask them some other time about the little flower of their fresco...

BREAD AND CIRCUSES

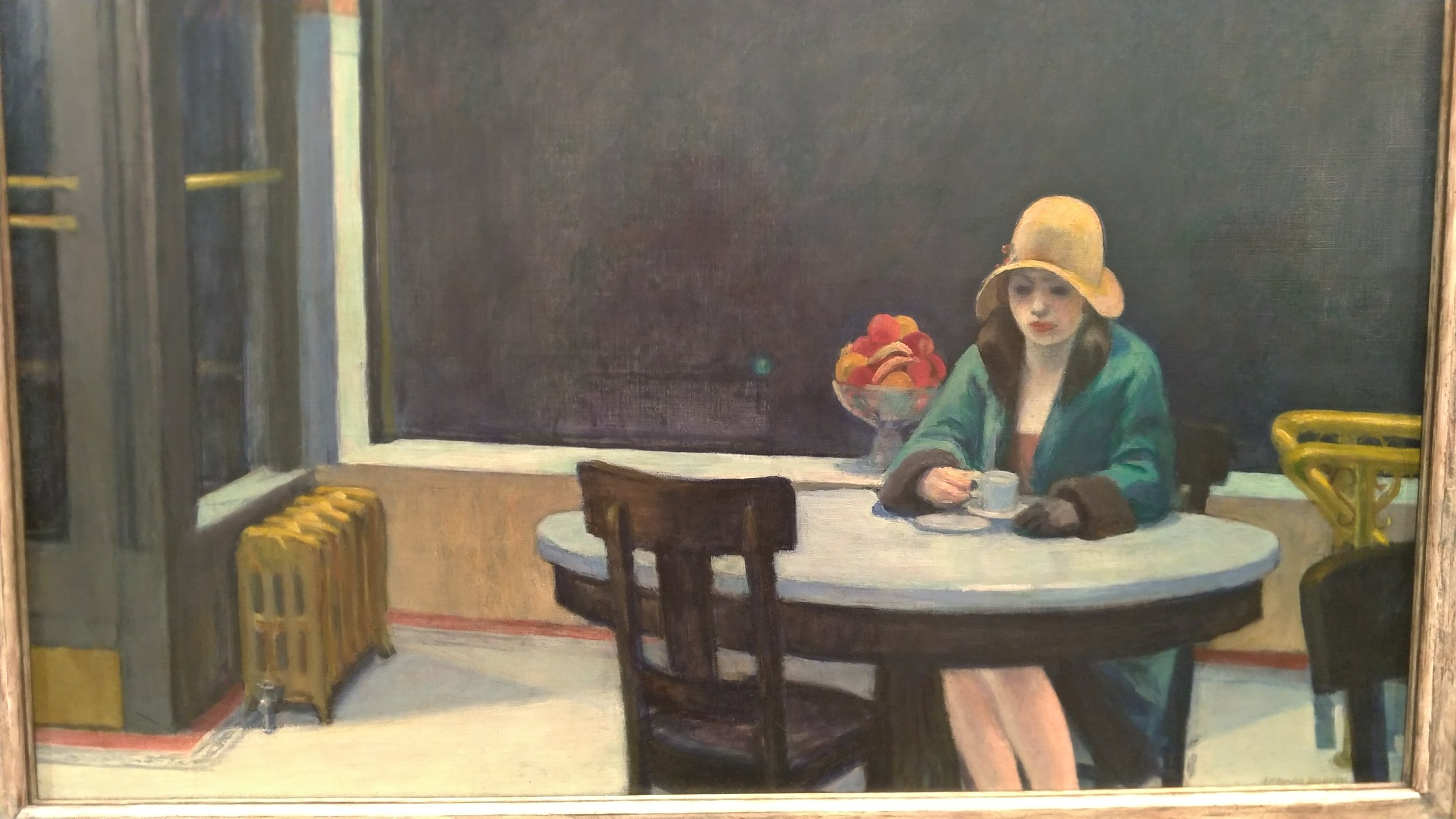

Now I have to go to dinner to the nearby house. But is it ever possible to focus on your food when the wall is adorned with the most exquisite mosaic that can ever be? And yet, right here, where Neptune and Amphitrite are posing extremely shiny, used to be the open-air summer dining area of this wealthy family. A sea shell spreads like a fan on the upper part of the composition, exalting its glorious palette (royal blue, light blue, burgundy, aquamarine, almond green), graced by twining sea and vegetal motifs.

Unfortunately the guards lock the space before sunset. Although I did not spend the night at Herculaneum, I do feel as if I've lived there, since its inhabitants opened their houses to me and granted me the freedom to dream their life.

Return to the underground cave: having reminisced both on the throbbing city above as well as on the dolce vita of the neighboring Herculaneum, I hope tomorrow I will be able to board the goodbye train, taking in the Gulf of Naples, towered by Vesuvius in the background.

This essay first appeared in Greek in the TA NEA newspaper (in print and online) on September 2, 2023.

It was reproduced by HellasJournal.com.

Το κείμενο αυτό πρωτοδημοσιεύτηκε στην εφημερίδα ΤΑ ΝΕΑ (έντυπη και ηλεκτρονική έκδοση) στις 2 Σεπτεμβρίου 2023.

Αναδημοσιεύτηκε από το HellasJournal.com.

Για να διαβάσετε το ελληνικό κείμενο, κάντε κλικ εδώ.