Manna from MoMA

In a period of low motivation to produce intellectual work (the brain is boiling, yet I'm having a hard time channeling the boil into one specific path), an invitation to a MoMA temporary exhibition with triple exclusivity – members only, for one evening only, and beyond the regular opening hours – came like manna from heaven. Courage, comrades: you'll be surprised with what the incentive to avoid the usual popular museum crowds can force us to accomplish. Within a split sec, I was at West 53rd Street.

As if procrastination were not enough to throw you into the swamp of inertia, recently I have been befriended by another member of the Association of Intellectual Productivity Saboteurs: difficulty concentrating. Great – that's the last thing I needed now. And yet, miraculously, MoMA got me covered on that one too: it didn't simply lure me in with a use-it-or-lose it offer; it had also made sure the offer consisted of artwork that makes you concentrate instantly – satisfaction guaranteed.

Admittedly, there was a third component to the mix for which I humbly bear sole responsibility: zero expectations. I had never heard the name Jack Whitten before and, purposely, I tried not to read anything about him so that, on one hand, I would be able to discover the artist by myself, and, on the other, I would not come with expectations that risked not being met – a well-known source of misery. I went tabula rasa.

Bingo: upon coming across the first paintings, my heart already starts to flutter. Delicious yellows and pinks, splendid light-blues – color blinds you and grabs you through lines, surfaces, shapes. I look at the title of an attractive light-blue abstract landscape, and wouldn't you know: “Mirsinaki Blue.” We learn that the Black artist, born in Alabama in 1939, called Crete his second home (after New York City) starting in 1969, and he spent all the summers of his life there, up until his death (2018). Mirsini is the name of his daughter.

The manual-labor aspect of painting

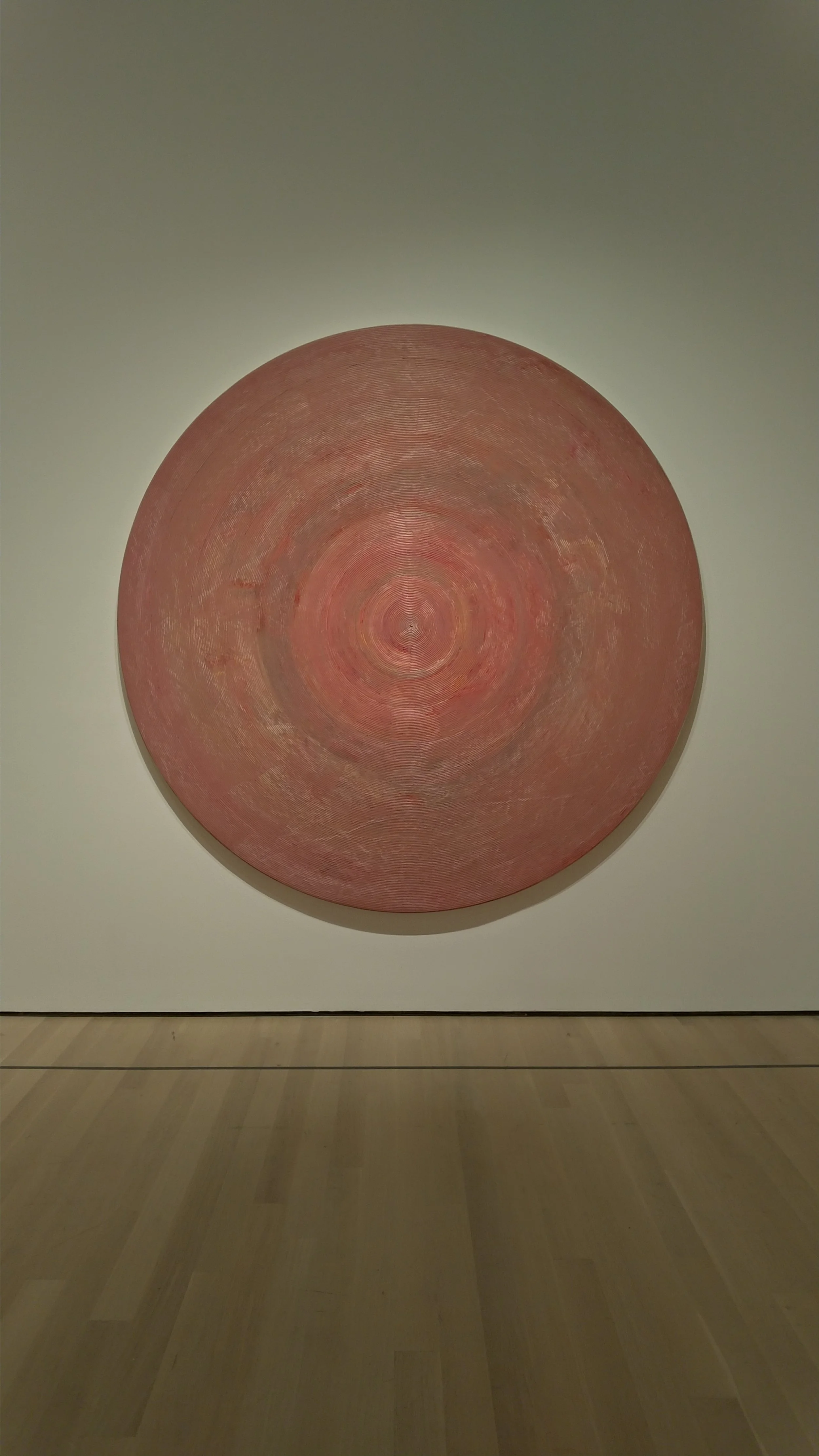

In front of the pink spiral disk (“Four Wheel Drive,” 1970), I felt as if I had discovered a treasure; the other visitors were passing by, I stayed there, magnetized – the joy of form. Enchanted by the strange, striated, as if ribbed landscapes, I go closer (several paintings are of monumental dimensions), and I observe the unusual texture. But how does he do it? How is it possible that the brushstrokes are so three-dimensional, the surface so raised, consisting of very fine parallel lines so geometrically perfect, as if drawn by some sort of machine?

Well, it turns out that this is exactly the case: Whitten has invented a very large “rake” of sorts (he calls it the “Developer”) in order to create his paintings. By dragging, harrowing the wooden device onto layers of poured paint, he drives, manipulates color onto his work surface (on ground level) in order to create his almost relief, sculptural paintings. The Developer's edge varies (squeegees, teeth, blades), and so does the kind of lines the “rake” leaves and, therefore, the visual result. Furthermore, the mixing of colors that is born, is unique.

In a handwritten note from the artist, I had noticed that he was referring to unusually large quantities of paint, and I had wondered: why is he writing a whole letter to thank a donor for paint – exactly how much paint was he in need of? When I saw how the “rake” works, I realized that, indeed, he really needed huge amounts. Also, while originally Whitten's quote that he doesn't paint a painting, he makes a painting, had sounded to me somewhat eccentric, after I saw the photo in which he is dragging his 12-foot wide and weighing forty pounds Developer, the manual aspect of painting emerged in all its meaning.

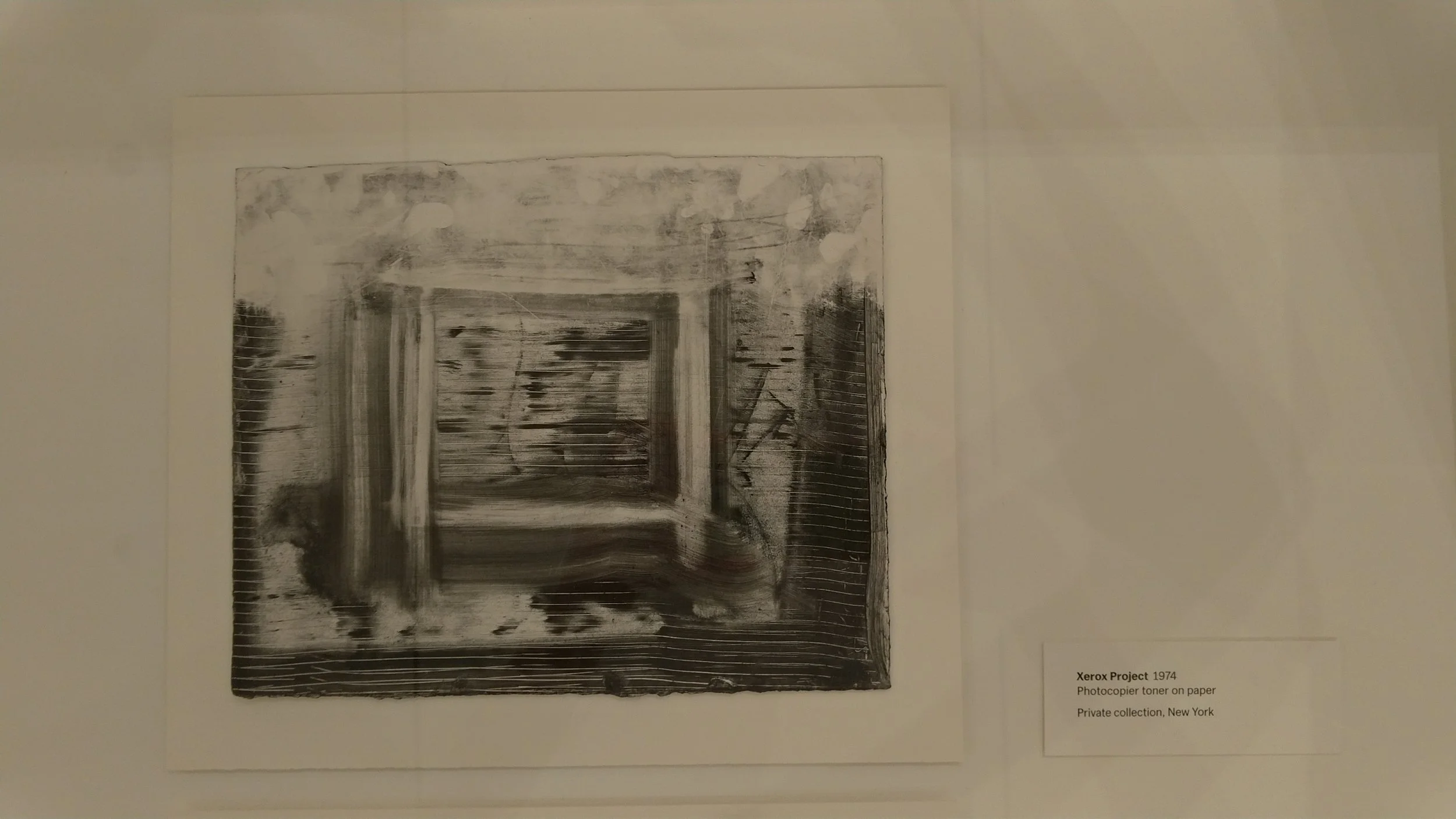

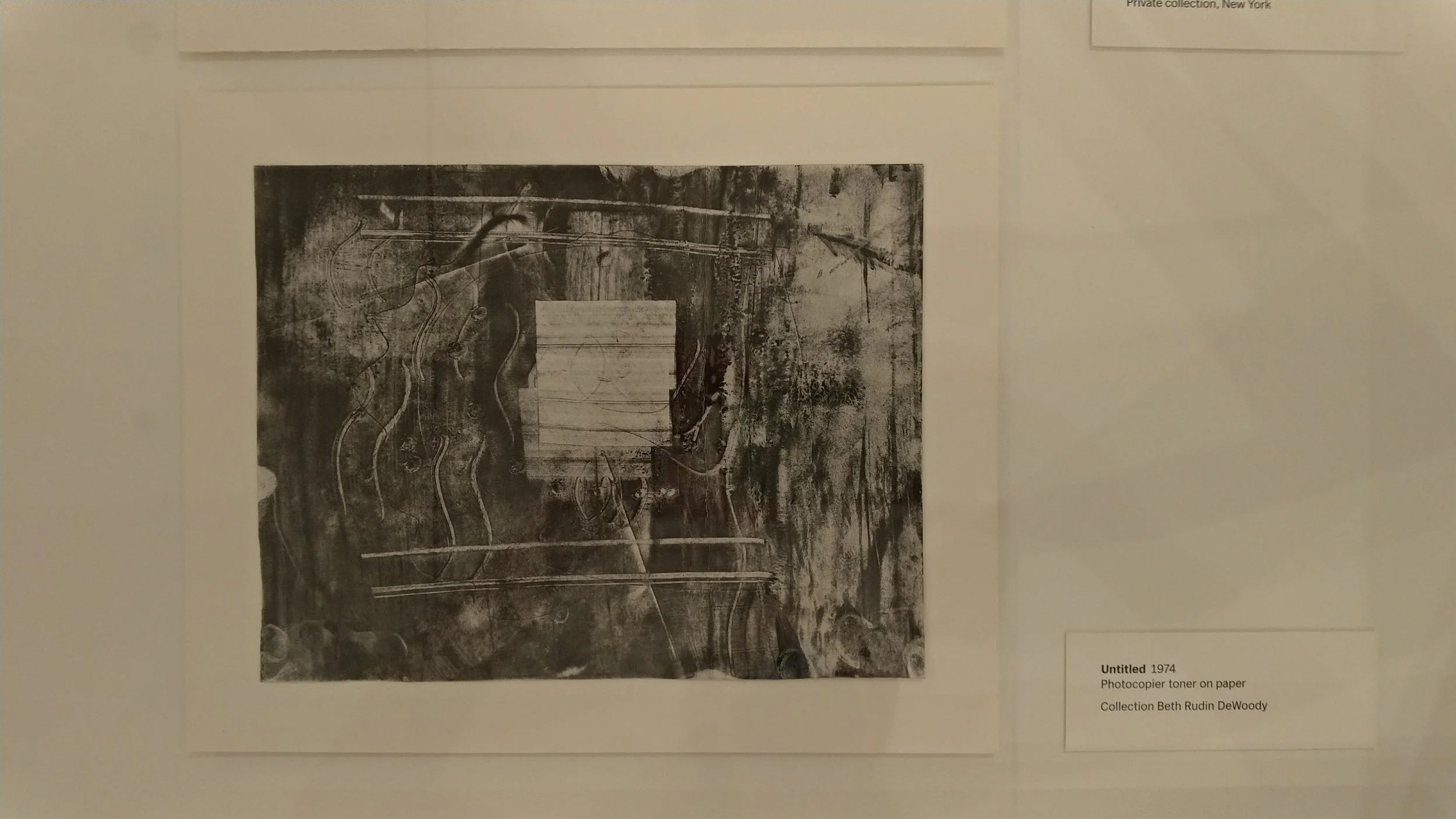

Playing with the copier

Next stop, the discovery of the experimentation with... the photocopier. Who would imagine that the colorless, cold corporate world would be able to fuel so directly an artist's work? In 1974, as part of a residency at XEROX, Whitten is given the opportunity to experiment with the features of the cutting edge technology of the printing and photocopying machines. He uses dry pigment – yes, toner, a new material at the time – in order to draw some eery black-and-white compositions, which, once again, make you wonder if some type of machine has been involved. Indeed, we learn that the “Developer” is back, this time as a mini-rake, with which the artist sprinkles or spreads the toner powder on the paper, giving a photographic feel to the drawings. (The ink leitmotiv goes a long way, since in Crete Whitten fished octopus that he not only cooked but also used their ink to paint.)

The collages: from here to eternity

But now all detail-obsessed folk are truly called. Found objects – a cassette, a fish, something like a comb, a piece of rope, something like a zipper - after having been immersed in or sprinkled with (I suppose) paint, leave their footmark or are captured as a whole onto Whitten's canvas. Appearing again and again is the honeycomb-like imprint of some sort of material which, though I'm guessing is bubble wrap, yet to me personally is reminiscent of the LEGO bases. From the studio, the home, or the sidewalk – the artist's surrounding space – the objects find their way to the collage-paintings and, thus, to eternity through their imprint. Those “remnants” make the spectators experience an unexpected connection with time. I'm thinking that I live in the same NYC streets, in the same place that supplied the raw materials for the collages that now hang like ghosts from the museum walls, time-capsules that, like bubblewrap, have trapped inside them forever something from the everyday life of that “then.”

The revelatory intimacy of lists

Parallel to all these dives and surprises and discoveries are “running,” like fellow travelers, like a music score, the painter's handwritten notes, his studio log: thoughts, observations, questions, reminders, and goals for a month or a lifetime are exhibited in cases among the works themselves. Who doesn't love a list? Who doesn't rejoice when facing the straightforward, alive way in which another human being comes to life, is revealed, when we see a simple list that they have written with their own hands? Of course one is free to ignore the lists, to let the artist's work alone speak for itself (instead of reading what the artist is saying they're pursuing with their work). And yet, in my opinion, in this case the lists enrich the experience.

I can't resist the temptation to cite a few excerpts:

STUDIO LOG 1988

10 MAY: I AM NATURE

18 SEPT: MY SPACE IS THE EXTREME MIDDLE

19 SEPT: I DON'T WANT SEXUAL METAPHORS

I DON'T WANT FORMALISTIC METAPHORS

I DON'T WANT POLITICAL METAPHORS

10 OCT: LOGIC IS A MYTH

STUDIO LOG 1992

8 NOV: THERE MUST BE SOME WAY TO BYPASS THE TIME ZONES: PAST – PRESENT – FUTURE = BEING

25 NOV: I SIT AND WATCH BENEATH MY FEET THE PASSAGE OF TIME

23 DEC: TO AVOID AT ALL COST:

1. FORMALISM

4. LITERAL

5. NARRATIVE

7. ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM

8. EXCESSIVE USE OF COLOR

11. OTHER ARTISTS

14. POST-MODERNISM

18. ART HISTORY

1 JAN '93: MY AMBITION IS TO REINVENT NATURE IN MY IMAGE

3 JAN '93: I WANT MY ART TO SERVE AS A BRIDGE: TO BRIDGE THE GAP THAT EXIST [sic] BETWEEN PEOPLE.

Aha: so, this Abstract Expressionism pioneer, in a specific moment of his career (1992), and while working on a specific piece, sets as a goal to avoid Abstract Expressionism.

The handwritten manifestos activate, accelerate the dialogue with the artist. And this is one of the reasons why we beat procrastination and lack of motivation, and we (still) go look at art. We exit - not simply our place but also the everyday flow of life – and we go to the museum in order to exit our self. And to enter into dialogue with something outside of us.

This essay first appeared in Greek in the TA NEA newspaper (online) on July 17, 2025.

It was reproduced by HellasJournal.com.

Το κείμενο αυτό πρωτοδημοσιεύτηκε στην εφημερίδα TA NEA (ηλεκτρονική έκδοση) στις 17 Ιουλίου 2025.

Αναδημοσιεύτηκε από το HellasJournal.com.

Για να διαβάσετε το ελληνικό κείμενο, κάντε κλικ εδώ.